A Biographical Sketch

of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy

Occasional Biographical Blog Posts

Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy was a German soldier who became a dedicated American, a professor who excoriated his academic colleagues for shirking their responsibility to society at large, and a Christian whose unshakable faith in the power of the word led him beyond the church. And yet a respected scholar of our day has called Rosenstock-Huessy “by Jewish standards an apostate, by Christian standards a heretic, and by academic standards an oddball.”

If apostates existed, they were Rosenstock-Huessy’s parents and maternal grandparents, none of whom were observant, or even religious. His maternal grandfather, Moritz Rosenstock, admitted Gentile students to the Samsonschule, Wolfenbüttel’s famous Jewish boarding school, and sent his daughter Paula to the local (Protestant) teacher’s college. She in turn refused to allow the circumcision of her only son. Rosenstock-Huessy was recognized as a completely orthodox Christian by Leo Weismantel, Carl Muth, Ernst Michel, and Joseph Wittig—Catholics in the vanguard of the movement later vindicated by Vatican II. Indeed, he was “Catholic” enough in the decade after his baptism that his wife Margrit’s native Protestantism presented difficulties in the first years of their marriage. He started out as an orthodox academic, if one who dared write that “language is wiser than the one who speaks it.” (In 2013, Hanna Vollrath reported that his early works on medieval law are still respected in their field.) He himself admitted that it was his friend Franz Rosenzweig who “forced him to renounce academe.”

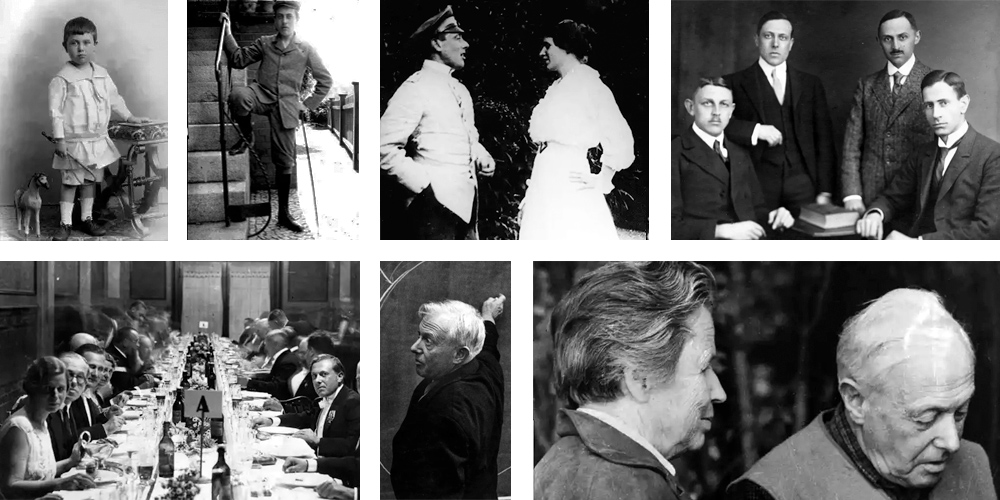

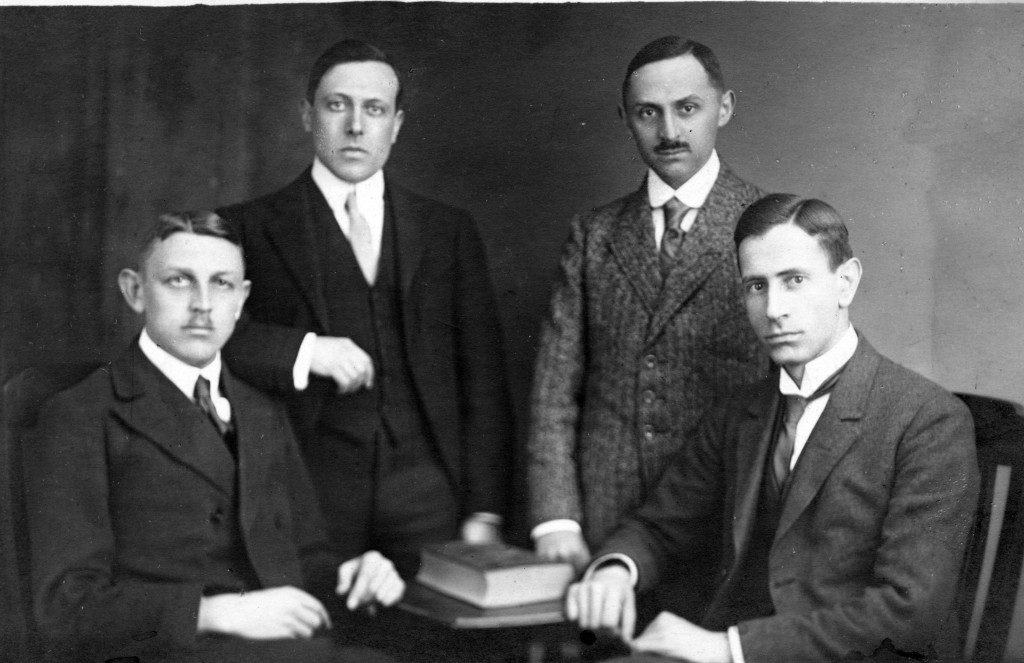

Eugen Moritz Friedrich Rosenstock was born in Berlin on July 6, 1888, the son of Theodor and Paula Rosenstock. Theodor had wanted to pursue a scholarly career, but his father’s death in 1870 left him responsible for his widowed stepmother and stepsister and so, with a loan from a wealthy uncle, Paul Waldstein, he started a small private bank; he eventually represented small bankers on the board of the Berlin Stock Exchange. Paula and Theodor had seven surviving children, of whom Eugen was their fourth child and only son.

After attending a school for wealthy families for several years, Eugen transferred to the Joachimsthaler Gymnasium, a school known for its rigorous academic standards, where he was not allowed to become the official “head of the class” (primus) because he was Jewish.

After attending a school for wealthy families for several years, Eugen transferred to the Joachimsthaler Gymnasium, a school known for its rigorous academic standards, where he was not allowed to become the official “head of the class” (primus) because he was Jewish.

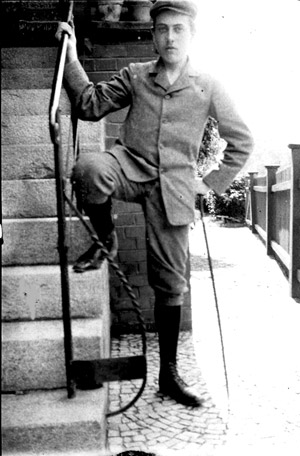

Although his passions were history and philology, Eugen took his father’s advice and opted for the law, studying at the universities of Zürich, Heidelberg, and Berlin. While he had flirted with the idea of becoming a Lutheran minister as a teenager, it was not until 1906, convalescing in Switzerland after severe appendicitis, that he accepted the advice of the aunt and great-uncle who had come to keep him company and formally become a Christian; and it was not until December of 1909 that he was baptized. It was not a drastic conversion: he always said that he was raised Christian in all but name – his family had always celebrated Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, singing Bach chorales on all three “German” holidays. However, his faith was central to his work in law and history, as well as his social action and adult education, pursuing what he called “the social embodiment of truth.” In 1909, at the age of 21, he received a doctorate in law from the University of Heidelberg. Three years later, he had become a Privatdozent, teaching constitutional law and the history of law at the University of Leipzig—at 24, the youngest Privatdozent in Germany at the time.

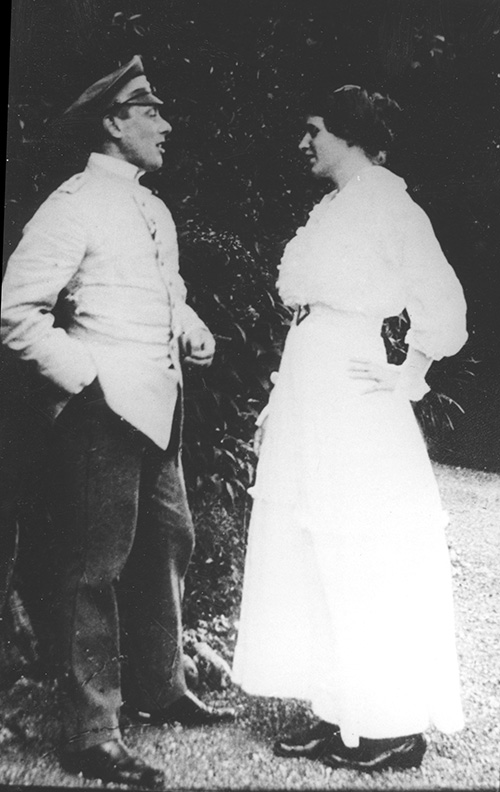

Early in 1914, Rosenstock went to Florence to help his brother-in-law Hermann Kantorowicz with a research project. There he met a young Swiss woman, Margrit Hüssy-Walthy, who was studying art history. While they declared themselves engaged the day they met, the outbreak of the war delayed their marriage until 1915; her parents agreed to regard them as married as of the originally planned wedding date (which his parents did not). Drafted at once as a lieutenant in logistics for the mounted artillery, he was stationed at or near the Western front throughout the war, including 18 months before Verdun. During this period he organized courses for the troops, including one that brought officers and enlisted men together as equals. In 1916, he and his friend Franz Rosenzweig, who was stationed on the Eastern front, exchanged their letters on Judaism and Christianity, later published in 1935 as a special appendix to the volume of Rosenzweig’s letters. The correspondence has long been recognized as a milestone in the history of “Jewish-Christian argument”; it was translated into English by Dorothy M. Emmet and published as Judaism Despite Christianity in 1968 (a new edition came out in 2011).

Early in 1914, Rosenstock went to Florence to help his brother-in-law Hermann Kantorowicz with a research project. There he met a young Swiss woman, Margrit Hüssy-Walthy, who was studying art history. While they declared themselves engaged the day they met, the outbreak of the war delayed their marriage until 1915; her parents agreed to regard them as married as of the originally planned wedding date (which his parents did not). Drafted at once as a lieutenant in logistics for the mounted artillery, he was stationed at or near the Western front throughout the war, including 18 months before Verdun. During this period he organized courses for the troops, including one that brought officers and enlisted men together as equals. In 1916, he and his friend Franz Rosenzweig, who was stationed on the Eastern front, exchanged their letters on Judaism and Christianity, later published in 1935 as a special appendix to the volume of Rosenzweig’s letters. The correspondence has long been recognized as a milestone in the history of “Jewish-Christian argument”; it was translated into English by Dorothy M. Emmet and published as Judaism Despite Christianity in 1968 (a new edition came out in 2011).

Rosenstock was keenly aware that World War I was a historical watershed. At the end of the war, he rejected offers to return to teaching the history of law at the University of Leipzig, to co-edit the ground-breaking Catholic periodical Hochland with Carl Muth, and to join Rudolf Breitscheid in drafting the constitution of the Weimar republic. Instead, he volunteered to help tackle the industrial unrest crippling the Daimler-Benz plant in Stuttgart and joined the engineer Paul Riebensahm in editing the first factory newspaper in Germany, the Daimler Werkzeitung. With Rosenzweig, Leo Weismantel, Werner Picht, Hans Ehrenberg, and Viktor von Weizsäcker, he founded the Patmos Verlag to publish work dealing with the changes in intellectual and religious life inevitably brought about by the calamity of the war. (One of the first books Patmos published was Rosenstock’s Die Hochzeit des Krieges und der Revolution (The Marriage of War and Revolution, 1920), a collection of essays on the consequences of Germany’s defeat and the inherent danger of not recognizing the bankruptcy of the institutions that had supported it, in which he warned of the danger of a “Lügenkaisertum,” a false revival of the Empire based on lies.) Members of the Patmos group later founded the magazine Die Kreatur (The Creature, 1926-1930), edited by Josef Wittig, Martin Buber, and Viktor von Weizsäcker; it was the first magazine ever jointly edited by a Catholic, a Protestant, and a Jew (and it may have been the last). Contributors included Rosenzweig and Rosenstock, Nicholas Berdyaev, Lev Shestov, Ernst Simon, Hugo Bergmann, Rudolf Hallo, and Florens Christian Rang, all of whom sought to offer an alternative to the idealism, positivism, and historicism that dominated German intellectual life.

In 1921, Margrit and Eugen had a son, Hans. In 1925, they legally changed their family name to Rosenstock-Hüssy, but it was not until after Eugen’s emigration to the United States that he used the hyphenated name professionally.

In 1921, Margrit and Eugen had a son, Hans. In 1925, they legally changed their family name to Rosenstock-Hüssy, but it was not until after Eugen’s emigration to the United States that he used the hyphenated name professionally.

Although never a Marxist, Rosenstock was invited by a group of trade union representatives to found and direct the Akademie der Arbeit (Academy of Labor) in Frankfurt/Main in 1921. This institution offered courses and seminars for blue-collar workers and bourgeois adults alike, and sought to erase the barrier between students and teachers. Rosenstock resigned in 1923 over differences with the people opposed to the changes in “education” he had introduced. He then lectured at the Technical University of Darmstadt in the faculty of social science and social history. Forced to return to academe to support his family, he remained committed to adult education.

In 1923, he was offered a job at the University of Breslau as a full professor of German legal history, a position he held until January 30, 1933. Rosenstock was awarded a second doctorate in philosophy from the University of Heidelberg that year for his scholarly medieval study, Königshaus und Stämme in Deutschland zwischen 911 und 1250 (The Royal House and the Tribes in Germany between 911 and 1250), which he had written in Leipzig and published in 1914. In 1925, Rosenstock published Angewandte Seelenkunde (Practical Knowledge of the Soul), the manuscript which had had such an impact on Franz Rosenzweig in 1916. In it he laid out his radical new method for the social sciences, based on the spoken word, and using grammar as a method to analyze human and social issues. He later called the approach “metanomics”; it remains at the heart of his later work, and is discussed comprehensively in his two-volume Soziologie (1956-1958).

In 1926, a friend of Rosenstock’s, the Catholic priest (and writer) Josef Wittig, was excommunicated and deprived of his professorship of church history. Rosenstock came to his defense and was able to achieve official emeritus status for Wittig, which safeguarded his pension. Together they published a church history for the postwar age: Das Alter der Kirche (The Age of the Church) in 1927-1928. The first two volumes contain historical essays on the two millennia of Church history, and the third documents the injustice of Wittig’s excommunication.

An inspiring teacher, Rosenstock was also responsible for adult education in the area around Breslau. With some of his students, he helped organize voluntary work service camps for students, farmers, and workers to address the appalling living conditions and atrocious labor conditions at coal mines in Waldenburg, Silesia: the “Löwenberger Arbeitslager.” (Many of the participants in the Löwenberg camps later formed the core of the Kreisau Circle, a German resistance movement against the Nazis, including Helmuth James von Moltke; Moltke’s cousin, Carl-Dietrich von Trotha; Rosenstock’s academic assistant, Horst von Einsiedel; and Adolf Reichwein.) In 1929, Rosenstock was elected vice-president of the World Association of Adult Education, in London.

While still teaching at Breslau in 1931, Rosenstock wrote and published the first of his major works: Die Europäischen Revolutionen—Volkscharaktere und Staatenbildung (The European Revolutions and the Character of Nations; 1931). This book, the vision of which had come to him before Verdun in 1917, showed how 1,000 years of European history had been formed by five hundred years of church upheaval and five hundred years of national revolutions that collectively made up a single that era that came to an end in World War I.

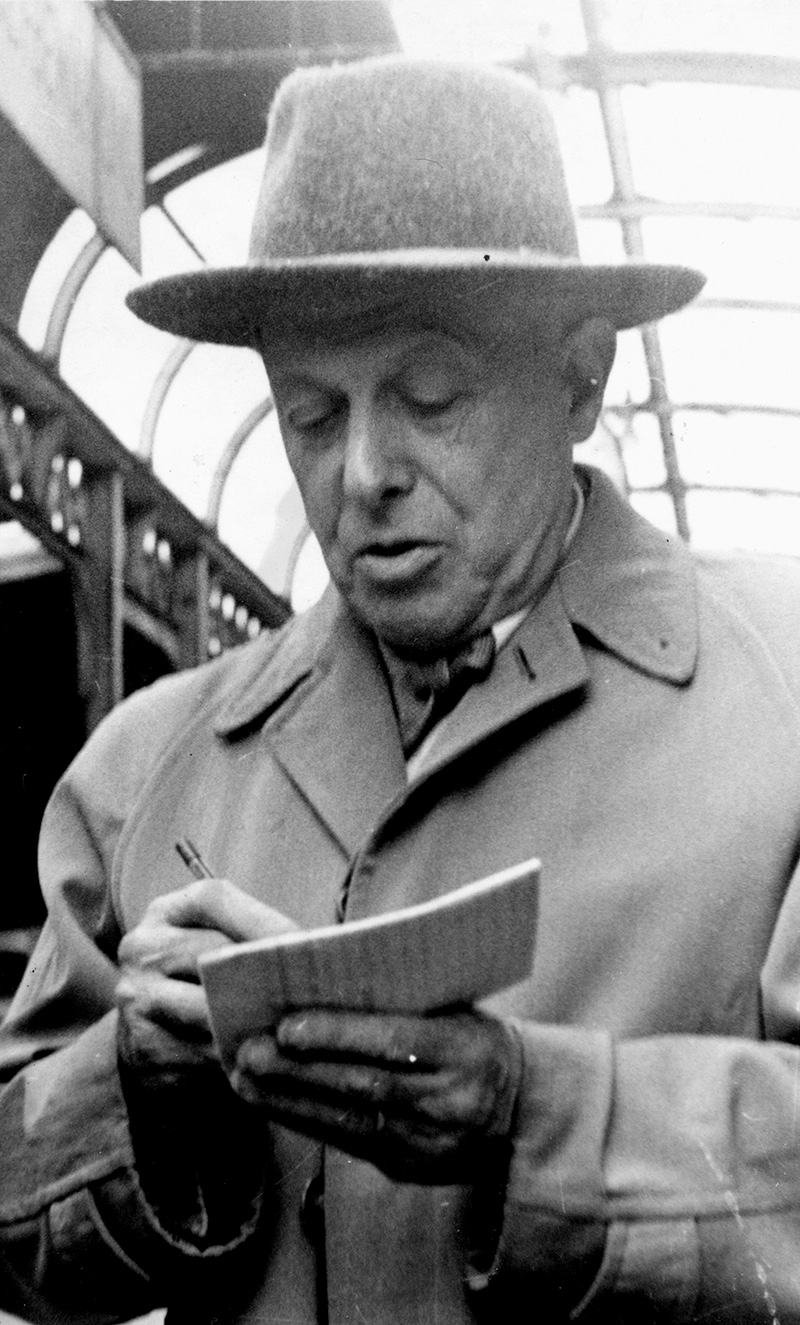

On January 30, 1933, Germany fell to National Socialism. Rosenstock resigned from the university at once, but stayed in Germany to arrange an extended leave of absence from the university. With the help of C. J. Friedrich, professor of government at Harvard University and the only person Rosenstock knew in the United States, he was invited to Harvard as a guest lecturer in government; he was subsequently appointed Kuno Francke Lecturer in German Art and Culture and then taught in the history department.

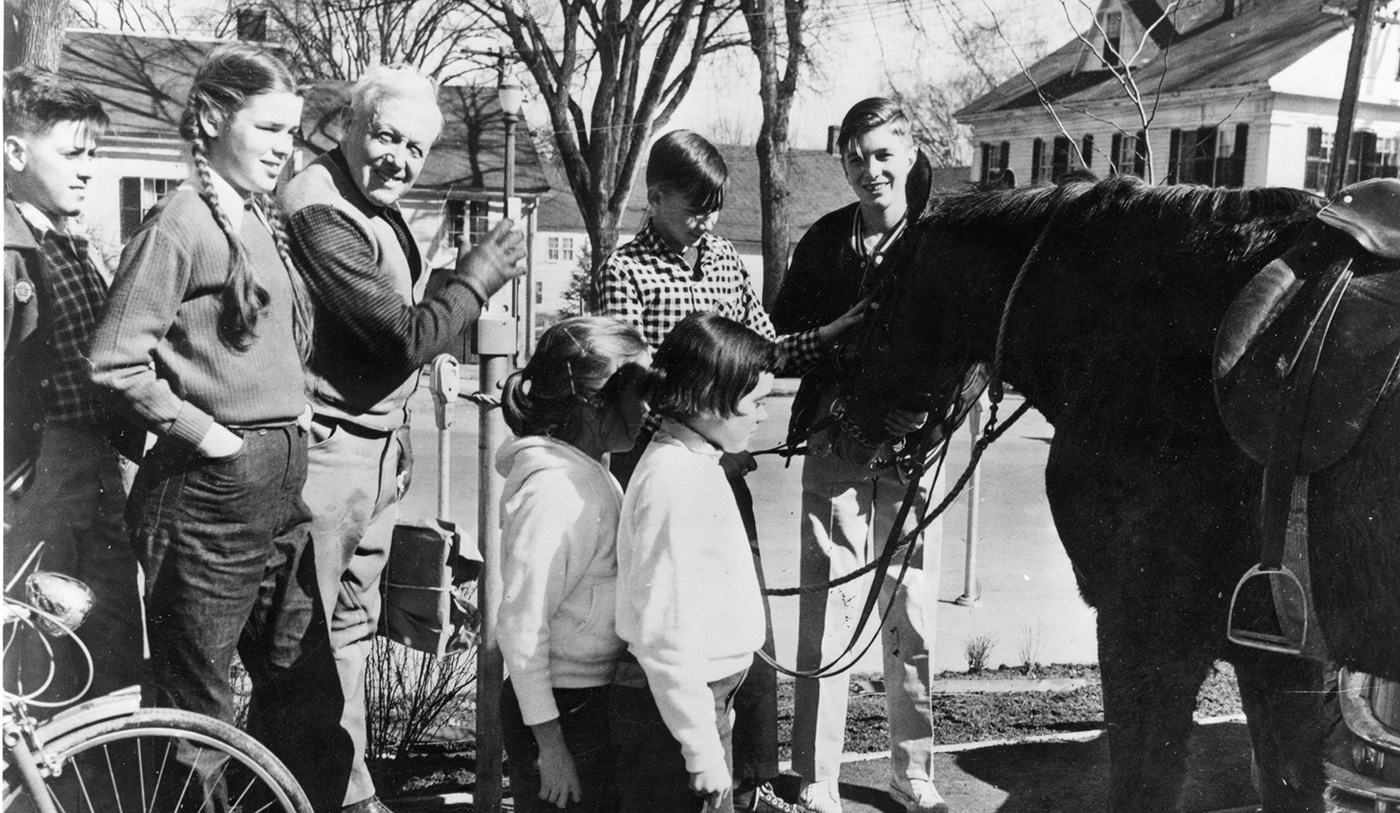

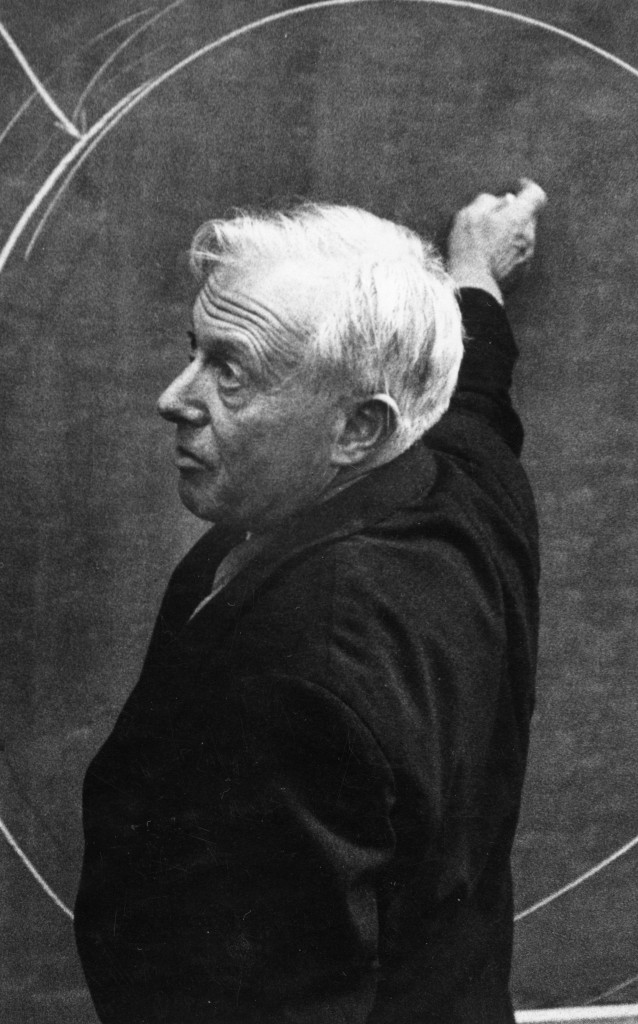

It was at Harvard that Rosenstock-Huessy encountered the strongest opposition to his ideas in social history, based as they were on the pivotal role in world history of Christianity. Rosenstock-Huessy frequently spoke of faith in class and attacked the myth of pure, objective academic thinking (in his ensuing disagreements with the Harvard history department, Alfred North Whitehead was his staunch supporter). In 1935 Rosenstock-Huessy accepted an appointment as professor of social philosophy at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. He made his home in nearby Norwich, Vermont. He taught at Dartmouth until his retirement in 1957, inspiring a generation of students.

It was at Harvard that Rosenstock-Huessy encountered the strongest opposition to his ideas in social history, based as they were on the pivotal role in world history of Christianity. Rosenstock-Huessy frequently spoke of faith in class and attacked the myth of pure, objective academic thinking (in his ensuing disagreements with the Harvard history department, Alfred North Whitehead was his staunch supporter). In 1935 Rosenstock-Huessy accepted an appointment as professor of social philosophy at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. He made his home in nearby Norwich, Vermont. He taught at Dartmouth until his retirement in 1957, inspiring a generation of students.

Rosenstock-Huessy had made important friendships in Cambridge that sustained him through his “exile” in New Hampshire. Henry Copley Greene and his wife, Rosalind Huidekoper Greene, helped him reforge his earlier book on revolutions for an American audience; the reimagined book became Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man (1938). Their son-in-law, George Allen Morgan (one of Whitehead’s students and the author of the classic What Nietzsche Means) helped assemble The Christian Future or the Modern Mind Outrun (1946). At the urging of prominent figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Dorothy Thompson, President Roosevelt asked Rosenstock-Huessy to lead the creation of a special training camp for leaders of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Vermont. Involving students mostly from Dartmouth, Harvard, and later Radcliffe, its purpose was to train young leaders for an expanded program that, instead of isolating unemployed youth in work-service programs, would bring volunteers from other walks of life to join them. A pre-existing CCC “side camp” near Sharon, Vermont, was chosen and named Camp William James, in honor of that philosopher’s search for a “moral equivalent of war.” The camp enjoyed a short term of success but was disbanded when the United States entered World War II. Camp William James’ model of voluntary work in service to communities in need has been cited in connection with the development of the Peace Corps.

After World War II, Rosenstock-Huessy was a frequent guest professor at universities in both the United States and Germany, lecturing and writing well into his 70’s. In 1956 and 1958, he published a revision of his early Soziologie, incorporating in the second volume his work on a universal history for mankind which runs through his Dartmouth lecture courses. In 1963 and 1964, he published a two-volume compendium of his work on speech, Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts: eine Leibhaftige Grammatik in vier Teilen (The Speech of Mankind: An Embodied Grammar in Four Parts, 1963-1964). His work includes 40 books and hundreds of essays and articles, as well as the hundreds of hours of recorded lectures (almost all of which may be read or heard on this site).

After World War II, Rosenstock-Huessy was a frequent guest professor at universities in both the United States and Germany, lecturing and writing well into his 70’s. In 1956 and 1958, he published a revision of his early Soziologie, incorporating in the second volume his work on a universal history for mankind which runs through his Dartmouth lecture courses. In 1963 and 1964, he published a two-volume compendium of his work on speech, Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts: eine Leibhaftige Grammatik in vier Teilen (The Speech of Mankind: An Embodied Grammar in Four Parts, 1963-1964). His work includes 40 books and hundreds of essays and articles, as well as the hundreds of hours of recorded lectures (almost all of which may be read or heard on this site).

Margrit Rosenstock-Huessy died in 1959. In 1960, Freya von Moltke, widow of the German resistance leader Helmuth James von Moltke, came to share Rosenstock-Huessy’s life in Vermont. Rosenstock-Huessy died on February 24, 1973 (Mrs. von Moltke lived on at “Four Wells” until her death in 2010).

Rosenstock-Huessy’s extraordinary insights continue to influence the lives of a growing number of people from around the world and from all walks of life.

Occasional Biographical Blog Posts