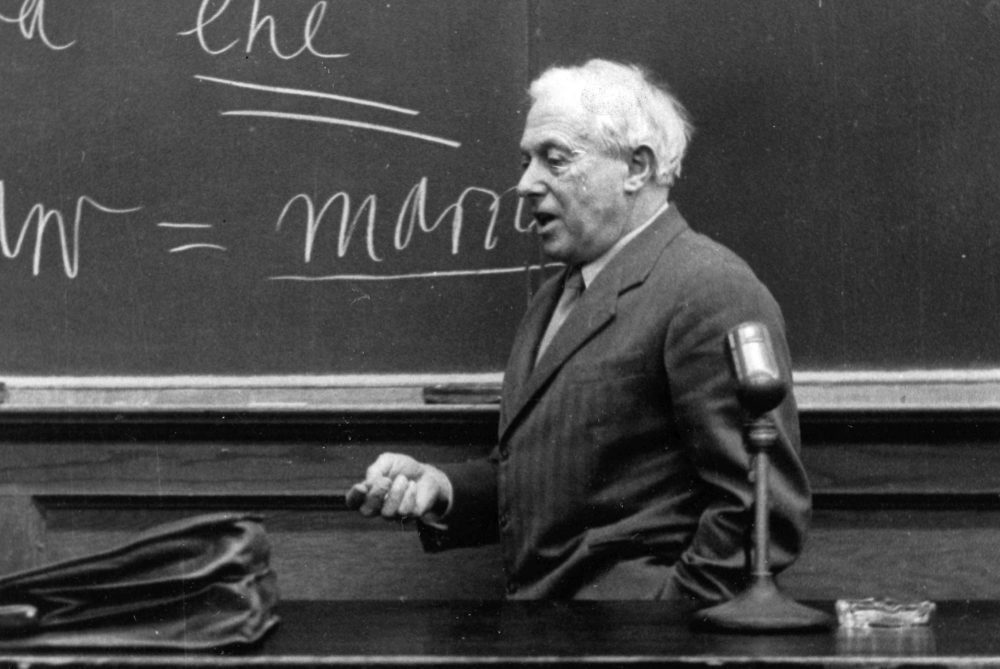

Volume 18: Universal History (1957)

Twenty-nine 1-hour lectures.

Man is not created out of clay and out of the living breath only, but out of the name which another person faithfully, and believingly, and lovingly bestows on him… The power to name is the divine power, gentlemen. And the power to bestow the right title on us comes always to any human being as a revelation.

God is the power that makes men speak. We know nothing else of God. You can explain nature by nature. By electrons, by neutrons, and neutrons by protons, etcetera. You can explain the world without God. You cannot explain your own power to make a declaration of love, and a declaration of war by anything but the divine power to speak… every word you speak has consequences in time.

And these consequences go far beyond your own lifetime, and they originate from time immemorial in the words you use… To speak means to create, or it means to deny creation.

—March 5, 1957

In Universal History (1957), Rosenstock-Huessy addresses the social inheritance of acquired characteristics, the sociology of historical change, and the generational shift of each new way of life. Individual lectures feature war and the tribes, the cost of settlement, fatherhood and Israel, the difference between “people” and “public,” and the definition of saints.

Lecture 3 contains a good presentation of the purpose of a universal history and its importance in creating the future. Lecture 11 has a classic Rosenstock-Huessy presentation on the power of speech.

There are several lecture series with this title.

All of them have the same premise as Out of Revolution, in that they seek to express the unity of history. But here Rosenstock-Huessy proclaims more than the unity of the 1,000 years of European history–he argues for the movement of the spirit through the entire history of mankind, “from Adam to the last judgment.” Our own story is told through the lives of our revolutionary ancestors: the tribes, the astrological empires, the Jews, and the Greeks, all of whom are honored not only for their enduring and continuing contributions to that history, but for having once and for all broken new ground.

Rosenstock-Huessy defends both the existence and the meaning of the Christian era. Indeed he names Christ as the turning point of history, the culmination of the yearnings of the ancient world and the redemption of its achievements, as well as the cornerstone of our hopes for the unity of mankind. Like Augustine before him, he sees the four ages of the ancient world succeeded by the millennia of the Christian era, in which one God superseded the many gods, one world was forged out of our competing empires and nations, and one great society is to be born of our many warring social forms. The history of mankind is retold as relay race in which each age or generation enters, claims, and incorporates new territory.

(Much of the material in these courses is available in German, in far greater detail, in the second volume of Soziologie. A translation of that second volume is in preparation.)

-

Lecture 01

-

Lecture 02

-

Lecture 03

-

Lecture 04

-

Lecture 05

-

Lecture 06

-

Lecture 07

-

Lecture 08

-

Lecture 09

-

Lecture 10

-

Lecture 11

-

Lecture 12

-

Lecture 13

-

Lecture 14

-

Lecture 15

-

Lecture 16

-

Lecture 17

-

Lecture 18

-

Lecture 19

-

Lecture 20

-

Lecture 21

-

Lecture 22

-

Lecture 23

-

Lecture 24

-

Lecture 25

-

Lecture 26

-

Lecture 27

-

Lecture 28

-

Lecture 29